Introduction

Welcome back! In my first post I outlined the crucial first steps when developing a Return to Play (RTP) protocol: relationships, communication, and integrating the multidisciplinary team. If the ultimate goal is to improve the long-term welfare of the athlete, it can only happen by improving the relationships with the performance team first; adopting a common language and establishing standardized lines of communication; and outlining everyone’s role to maximize each members’ strengths to work under a shared vision that advances the athlete back to high function. It is paramount to address these in order to create sustainable relationships that allow your system to flourish. This is a fluid and ever-evolving process that doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time, investment, and ultimately letting go of your ego for the higher purpose of helping the team and athlete. However, the benefits can lead to improved function and execution that further advances the organization. As Fergus Connolly stated at exhaustion in his book Game Changer, “…human beings are always the number one asset.”

Creating a Framework for Success

Once we have addressed the human factor, it’s time to adopt models that will guide the RTP process. In a 2016 Consensus Statement on Return to Sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy (1), they indicated the importance of using models to help understand and guide the RTP process. These models will create a framework that provides a transparent, collaborative, and evidence-based approach to progress the athlete. This involves adopting Athlete-Centered, Reconditioning, Shared-Decision Making, StAART Framework, and Criterion/Performance-Based models.

Athlete-Centered Model

Traditionally, rehabilitation has placed the Surgeon, Team Physician, and/or Athletic Trainer as the focal point to direct all protocols throughout the RTP process, relegating other professionals to a subservient role, and taking the focus off the athlete. This is where ego tends to rear its ugly head, leading professionals to argue over their own territory, ultimately leaving the athlete with insufficient care. This approach fails to account for the one constant in everyone’s setting, the athlete. The athlete should always be at the center of the management process (2). This is echoed by the National Athletic Trainers Association, in which they indicate the importance of “athlete-centered care” through the delivery of healthcare services that are focused on the individual athlete’s needs (3). Therefore, an athlete-centered model places the athlete at the center of the program, with all professionals working together to ensure the athlete attains his or her goals (4). Within this model, everyone has the athlete’s best interest in mind, respects and understands everyone’s role (as I stated in my previous post), and uses evidence-based practice within the framework of the RTP process. In order to have the athlete’s best interest in mind, the athlete must also be heavily involved in the process. This leads me to the four key habits of athlete-centered return to sport as outlined by King, Roberts, Hard, and Ardern (5):

Empower

Educate athlete about their injury

Consult athlete about management options

Develop short-term and long-term criteria the athlete agrees with

Engage

Encourage athlete to outline their objectives

Educate athlete on plan for RTP

Encourage athlete to use this information to contribute to the process

Feedback

Schedule regular meetings throughout process

Allow athlete to speak first to limit influence of other stakeholders

Summarize key action points and update progress

Transparency

Communication must be frequent and honest to manage expectations

Transparency allows for stakeholders to openly discuss issues/expectations

As you can see, this places the athlete at the center of the process, in which they have a major influence on their own progress. This fosters athlete autonomy, which has been shown to promote personal development, improve motivation and task performance, and subsequently improve rehabilitation outcomes (5). Ultimately, the athlete-centered model moves away from the fragmented approach to traditional rehab, to a more unified reconditioning model involving the athlete and all members of the multidisciplinary team.

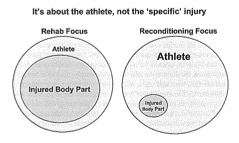

Reconditioning Model

So now you may be asking what the difference is between rehabilitation and reconditioning? Traditional rehabilitation has been focused on the isolated injury using a localized treatment modality, while disregarding total physical development. This process doesn’t always identify the “cause” of pain or injury, such as faulty mechanics, neurological deficits, or underlying structural issues (4). It’s not to say that traditional rehabilitation is bad. It’s not. During the acute period after an injury, it’s essential to restore tissue health, joint mobilization, and ligament integrity, while respecting homeostasis (6). However, we must take a more wholistic view in order to optimally prepare the athlete. With this in mind, a more modern approach needs to be both tissue specific and functional, with an emphasis on motor learning, reorganization, and sport relevance (2). This is the benefit of the reconditioning model, which is a performance-based and medically supported model for training athletes following injury or surgery (7). This takes a more comprehensive approach that pinpoints the root of the problem, while allowing the integrated multidisciplinary team to collaborate throughout the process. This allows the performance team to address all aspects of athletic development immediately post injury to better prepare and sustain the athlete for a return to competition. One of the biggest components of reconditioning is training around injury, with the aim of avoiding prolonged immobilization, which has been shown to have detrimental effects on muscle tone, strength, and structure (8). On the other hand, resistance training early in the rehabilitation process has been shown to be critical to the redevelopment of neuromuscular control and function, and the development of strength and endurance in injured tissues (9,10). With this in mind, emphasis is placed on what the athlete can do. This immediately integrates the medical team with the strength and conditioning coaches and coaching staff (2). Close coordination with trainers and coaches is essential, and all need to understand that the reconditioning phase is crucial to safely progressing the athlete back to competition. (11). As Bill Knowles states, “it is easy to get them back, but difficult to keep them back” (7). In an epidemiology of High School Sports-Related injuries from 2005-2014, it was concluded that of all the sporting injuries that led to medical disqualification, 60% were suffered during competition (12). This demonstrates the importance of a reconditioning model that bridges the gap between the medical team and the performance team to ultimately develop a more robust athlete who can sustain the demands of competition.

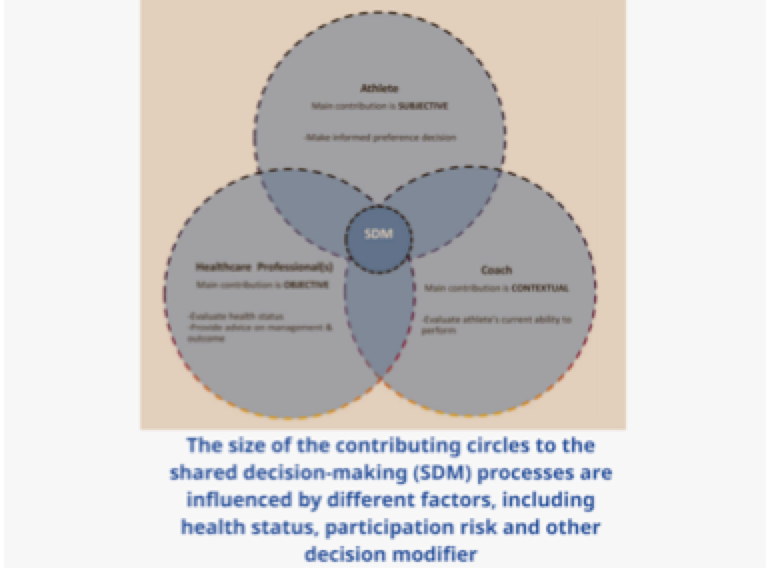

Shared-Decision Making Model

So, who’s decision is it anyway? As I mentioned above, in the past the Surgeon, Team Physician, and/or Athletic Trainer was the gatekeeper and ultimate decision maker. However, times have changed. The RTP process now involves a multidisciplinary team navigating a complex situation in which roles can overlap. This has a high potential for conflict as decisions, opinions, and goals may differ among the parties involved (highlighting the importance of the elements outlined in my first post). External information and relationships have also been shown to play a significant role, as coaches family members, teammates, and friends can influence the decision-making process (13). Ultimately, the decision to further progress the athlete through the process, and eventually full clearance for competition, should be a decision shared by all contributing members of the performance team, as well as the athlete (13). This sentiment is shared by a number of publications (4, 6, 11) that indicate there is obvious overlap between professionals within the RTP process, and we need to get comfortable understanding no single person can do everything. Therefore, adopting a model that creates structure and transparency within a complex situation, especially given the circumstances under which a decision is made will always be different, is essential. This leads us to the 3-step decision-based model for RTP provided by Creighton, Shrier, Shultz, Meeuwisse, and Matheson (13). Shown in the Venn diagram above, this model allows all contributing members to evaluate the health status and risk of participation of an athlete at any point during the process, while considering factors involved in decision modification. The best part about this model is it allows risk assessment to be applicable at any stage of the process and by any member of the multi-disciplinary team, as long as there is effective communication (13). As I outlined in my first post, understanding and providing clarity on everyone’s role is imperative.

Athlete: main contribution is subjective-make informed preference decision

Healthcare Professionals (including S&C Coach): main contribution is objective-evaluate health status, provide advice on management and outcome

Sport Coach: main contribution is contextual-evaluate athlete’s current ability to perform

Ultimately, the shared-decision making model provides a formal structure and process to help guide interactions, while providing contributing members with an evidence-based rationale for decision making.

StAArt Framework

Once the athlete has cleared the functional criteria needed for each phase of the reconditioning model, a decision to return to sport approaches. As stated in the Shared-Decision Making Model, the decision of returning to sport is not one taken in isolation. It is a collaborative decision made by the entire multidisciplinary team, as well as the athlete being the final judge. This is where the strategic assessment of risk and risk tolerance (StAART) framework can guide members in making informed decisions, while gradually returning the athlete back to competition. Since the multidisciplinary team may have differing opinions on whether the athlete is sufficiently prepared to increase sport activity, the StAART framework provides a three-step framework to estimate risks associated with a return to sport. Along with being aware of the demands of the sport, this is where the achievement of carefully formulated objective criteria and monitoring load progression can provide tangible context to make better decisions. Using baseline measures, functional testing, and psychological readiness, as well as assessing both open and closed skills as it pertains to the sport, the multidisciplinary team needs to ensure the athlete can meet the physical demands of the sport without sustaining a reinjury (14). Below I have outlined each step of the StAART framework:

Evaluation of Health Status (Step 1): Evaluate health status of the athlete through the assessment of medical factors to provide information on how much healing of the injury or illness has occurred.

Evaluation of Participation Risk (Step 2): Evaluate risk associated with athlete participation. This is risk directly associated with athlete and sport, such as type of sport, position, and competitive level. can be risk of reinjury, use of risk modifiers, time of year (pre-season, conference play, playoffs), and social factors.

Decision Modification (Step 3): Decision Modification is set aside from the other steps because participation risk does not contribute information about Decision Modification, and Decision Modification cannot be used to determine RTP except in the context of participation risk. This includes time of year, internal and external pressure, and conflict of interest.

This process is repeated as the healing process continues and if the status of the athlete changes as they progress through the RTP process. Therefore, to reduce potential conflict between the multidisciplinary team, as well as maintain an objective approach, the StAART framework provides a transparent process to guide RTP decisions.

Criterion/Performance-Based Method

Historically, surgeons and physicians have used time as the major criteria when determining when an athlete should return to play. However, the calendar doesn’t optimally determine individual recovery rate and functional status (11, 15). In his book, The Checklist Manifesto, Dr. Atul Gawande indicates that “under conditions of complexity, not only are checklists a help, they are required for success” (16). Although we’re not necessarily working in life and death situations as Dr. Gawande does, we are working in complex settings which involve varying degrees of injuries, occurring in different sports, and most importantly, with different athletes. Adopting a checklist method to help guide our decisions through the RTP process can help ensure that nothing gets overlooked, while also safeguarding that the athlete meets the necessary criteria to advance. In a recent study, an evidence-based checklist approach was validated to reduce the chance of reinjury for athletes following ACL reconstructions (15). Prior to a return to play, patients underwent seven objective measures, including physical exam, functional testing (hop and agility testing, movement assessment), and functional outcome score. Among the findings of the study, checklist patients had a significant decrease in both ipsilateral and contralateral knee re-injury. As this study indicates, checklists and objective measures play an integral role in clearing the athlete, while reducing the chance of reinjury. Therefore, the progression of a reconditioning program should be based on functional criteria instead of being time based, with sport-specific functional testing determining the progression to the next phase (11).

Closing

“Excellence is a continuous process and not an accident”—A. P. J. Abdul Kalam. We must be strategic about how we create our process to minimize interference and maximize progression for the athlete. This involves optimizing a framework that provides a transparent, collaborative, and evidence-based approach to progress the athlete. Integrating the Athlete-Centered, Reconditioning, Shared-Decision Making, StAART Framework, and Criterion/Performance-Based models will serve to create objectivity within our process. Stay tuned for Part 3 of the Return to Play Conundrum, where I will establish a purpose, define the process, and outline how to create a plan.

Resources

(1) Ardern, Clare & Glasgow, Philip & Schneiders, Anthony & Witvrouw, Erik & Clarsen, Benjamin & Cools, Ann & Gojanovic, Boris & Griffin, Steffan & Khan, Karim & Moksnes, Håvard & Mutch, Stephen & Phillips, Nicola & Reurink, Gustaaf & Sadler, Robin & Silbernagel, Karin & Thorborg, Kristian & Wangensteen, Arnlaug & E Wilk, Kevin & Bizzini, Mario. (2016). 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. British journal of sports medicine. 50. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096278.

(2) Joyce, D. (2014). High-performance training for sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

(4) Falsone, S.,(2018). Bridging the gap from rehab to performance.

(5) King, J., Roberts, C., Hard, S., & Ardern, C. L. (2018). Want to improve return to sport outcomes following injury? Empower, engage, provide feedback and be transparent: 4 habits! British Journal of Sports Medicine. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099109

(6) Kraemer, William & Denegar, Craig & Flanagan, Shawn. (2009). Recovery From Injury in Sport: Considerations in the Transition From Medical Care to Performance Care. Sports health. 1. 392-5. 10.1177/1941738109343156.

(7) Joyce, D., & Lewindon, D. (2016). Sports injury prevention and rehabilitation integrating medicine and science for performance solutions. London: Routledge.

(8) Booth, Frank. (1987). Physiologic and Biochemical Effects of Immobilization on Muscle. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. &NA;. 15-20. 10.1097/00003086-198706000-00004.

(9) Kraemer, William & Ratamess, Nicholas & French, Duncan. (2002). Resistance Training for Health and Performance. Current sports medicine reports. 1. 165-71. 10.1249/00149619-200206000-00007.

(10) Järvinen, Tero & Järvinen, Teppo & Kääriäinen, Minna & Äärimaa, Ville & Samuli, Vaittinen & Kalimo, Hannu & Järvinen, Markku. (2007). Muscle injuries: Optimising recovery. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology. 21. 317-31. 10.1016/j.berh.2006.12.004.

(11) Dhillon, Himmat & Dhilllon, Sidak & Dhillon, Mandeep. (2017). Current Concepts in Sports Injury Rehabilitation. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 51. 529. 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_226_17.

(12) Tirabassi, Jill & Brou, Lina & Khodaee, Morteza & Lefort, Roxanna & K Fields, Sarah & Dawn Comstock, R. (2016). Epidemiology of High School Sports-Related Injuries Resulting in Medical Disqualification: 2005-2006 Through 2013-2014 Academic Years. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 44. 10.1177/0363546516644604.

(13) Creighton, David & Shrier, Ian & Shultz, Rebecca & H Meeuwisse, Willem & O Matheson, Gordon. (2010). Return-to-Play in Sport: A Decision-based Model. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 20. 379-85. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181f3c0fe.

(14) Gabbett, Tim & Benton, Dean. (2008). Reactive agility of rugby league players. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia. 12. 212-4. 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.08.011.

(15) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/03/180306101654.htm

(16) Gawande, A. (2014). The checklist manifesto: How to get things right. Gurgaon, India: Penguin Random House.