I recently spoke at the UMBC Sports Performance Seminar regarding athlete load monitoring. I find that in all my years of coaching I rely heavily on the monitoring process to help drive decisions in the training I am prescribing, getting to know my athletes and clients better, and tracking if the programs I am writing are having the desired effect.

So let us start out with one of the ways you can monitor yourself , your clients, or your athletes and how you can make some decisions about the training status.

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) is one of many ways in which we can monitor the loads we are prepared for and our fitness or fatigue levels.

RPE has been around since ~ 1950’s and I believe was first used in the endurance community. RPE is an internal load metric and is calculated by taking the average level of difficulty for the entire session and multiplying it by the session duration in minutes. The most common RPE scale used is this one:

Most research suggest a 30 minute reporting window from the time you completed your session to the time you record your RPE. This allows your body time to adjust so that your not reporting on the very last thing you just completed. I have found at least 1 study that states there is no difference in a 10 minute reporting window vs a 30 min reporting.

Before you start to implement the RPE scale for your everyday training you will want to anchor it. Typically for my athletes and clients I have them first report on their RPE after performing a maximal fitness test. For some this has been a YoYo IR1, for others it has been a 1-mile test, and for others maybe a KB snatch test and for the CrossFit community maybe it is one of the signature workouts that you value. What ever you use, you will want to be able to repeat it in the future and have a submaximal version that you can use to “re-test” as a way to track your progress. The submaximal version will come back to be incredibly helpful to get insight into a fatigue indicator or an improvement indicator. Your submaximal version should last no more than ~ 6 minutes.

RPE is categorized as an internal load marker, and because of its versatility is considered a “Gold standard” of monitoring. It is a marker that you will never have to update, and the units will always remain the same.

Whether you are using this for yourself, your team, or your clients, RPE is NOT a group project. It is how you felt the session was, not what you wanted it to be, what it should have been, or what your training partner thought it was. It is not to be judged, it is only to be used for information. Over time I feel that RPE can also be used as a communication tool to prescribe intensity, but I would not suggest you roll this out right away with your clients or athletes. Give it some time for the language and feelings to solidify before you add more pieces to the puzzle. Eventually it is a great way to teach, communicate, and allow for auto regulation of any session.

One of the ways you can organize this is to set up a simple Google forms sheet where you input the type of session (ie run, practice, lift….) Have a scale of 1-10 and a place to input the duration (in minutes only). Once you have created the form, send the short URL link to the appropriate party and have it put in the calendar on their phone (or your phone if you are going to monitor yourself) with an alarm everyday. It literally takes 8 seconds to open, fill out, and be sure the results were submitted. The information that can be gained from this 8 second investment overtime can be profound. Once the results are submitted into Google forms, you will basically have an excel file being created for you that you can then add in some simple calculations to track your loads.

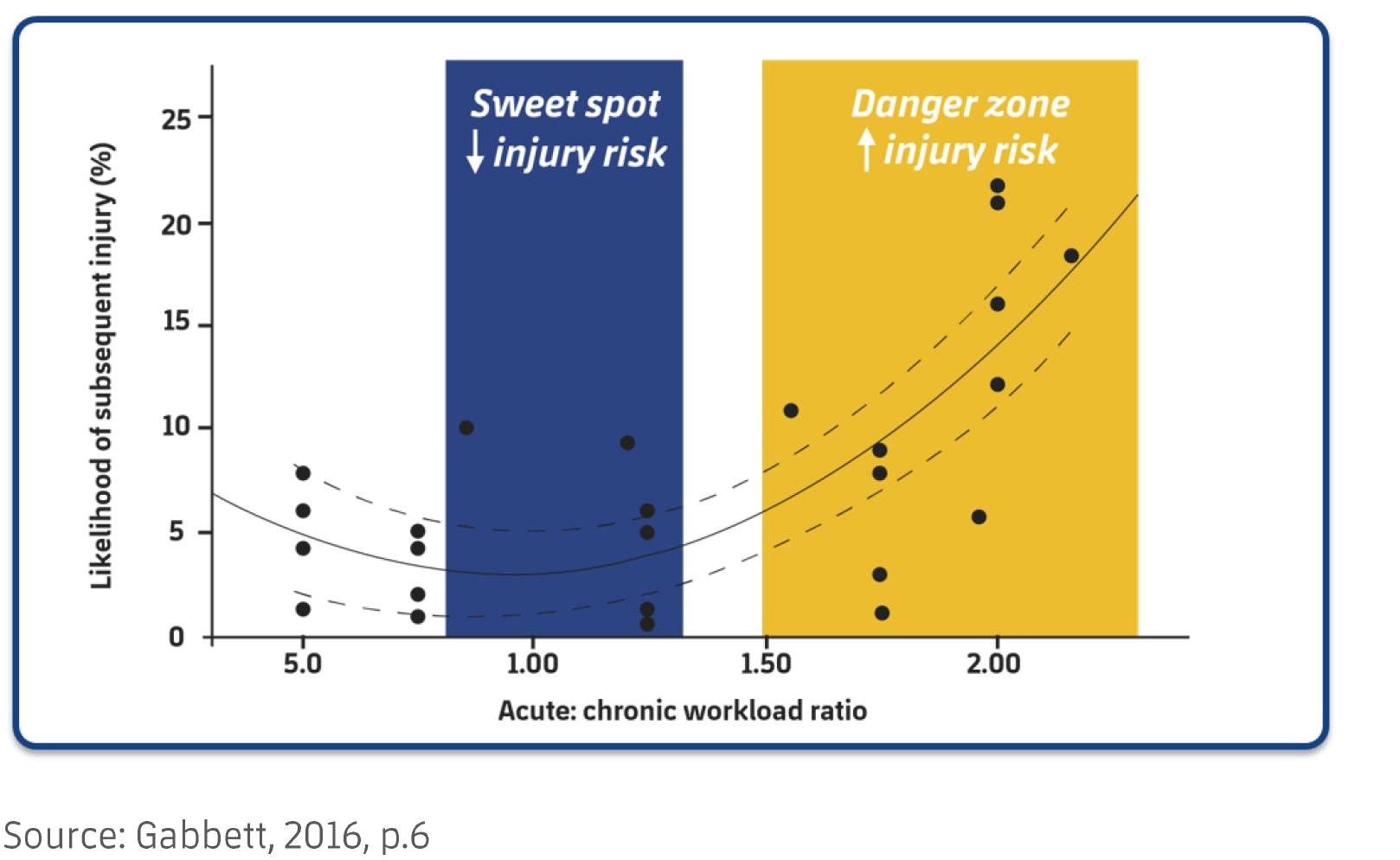

As you are tracking your daily loads and accumulating this overtime you will have significant data that you can refer back to. One of the markers I mostly use for an athletes lifetime training history or an athletes training history in the current phase is the Acute to Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR). Dr. Gabbetts research points out to a sweet spot of .8-1.3 for this ratio. That “Sweet spot” tells us that on AVERAGE we are protected from injury and are in a proper loading cycle. This is what his research has shown on average, but there are always outliers that we will get to in a later post.

Systematically building high chronic workloads protects us from injury and allows us to improve our overall fitness. Improving our overall fitness is about preparing the body for the sympathetically driven stress of life and improving our overall health and wellbeing. Tracking the physical loads is one way to be aware of our preparedness for upcoming loads, our fatigue and our improvement. When our ACWR is too low, what you see is an increased risk of injury just as when our ACWR is too high. So, decreasing the load may not always be the correct response.

Below are some of the calculations to use with RPE

sRPE Training Load = RPE X Duration in Minutes

Acute 7 day load = SUM of the 7 days of training (including today and the 6 days prior)

Chronic 21 day load = Average the Acute training load

ACWR = (Acute 7 day) / (Chronic 21 day)

One of the reasons this is important is that a spike in your Acute load can leave you at an increased risk of injury for up to 4 weeks, it is definitely not just about making it to your next off day and you are in the clear. Workload spikes can linger around leaving us more susceptible to injury for days and weeks.

Now, back to our fatigue and improvement indicators with your submaximal protocol. An increase of 2 pts or more on a submaximal protocol is an indication of fatigue, while a decrease of 1-2 points is an indication of improvement. If we are performing a submaximal protocol on a regular basis it is one more variable allowing for checks and balances.

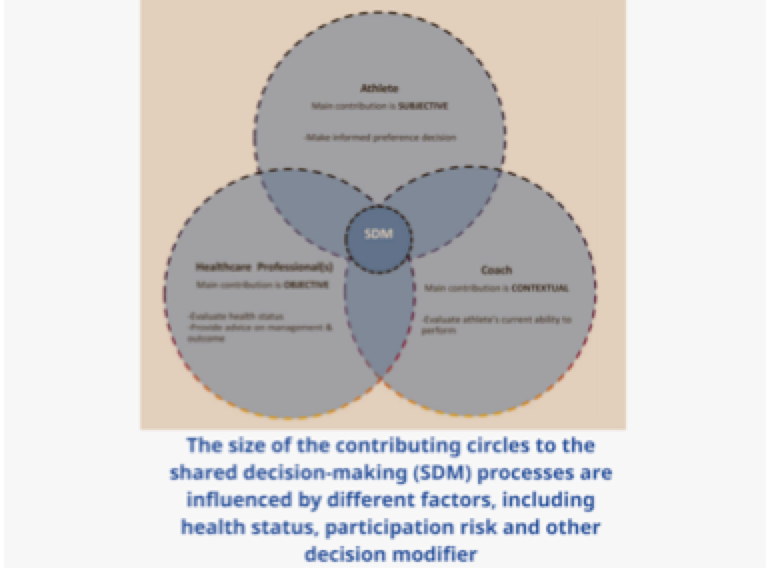

Unfortunately at some point we all might be injured and tracking your RPE will give you, or the sports medicine professional, or the sports performance professional detailed information of the loads you were under and how you were experiencing them. It can give an indication of how long you might need to take before you are 100%. Lets say you have been sidelined with an injury for 4 weeks, and your training has diminished significantly, if you go back to your old training loads based one tissue healing alone, you will likely be subjecting yourself to a workload spike. Just a few paragraphs before I mentioned that workload spikes can leave us at risk of an injury for up to 4 weeks, when you add on-top of that spike the fact that previous injury history increases our susceptibly to future injury, you could be dusting off the welcome mat to another injury.

In short, tracking your RPE can:

Give you insight into the loads you are prepared for

Serve as a language marker for prescribing training intensity

Provide markers indicating fatigue or improvement

Greatly improve the return to performance process and success

References:

BioForce Conditioning Coaches Certification Course – Joel Jamieson 2018

Workload Management and Injury Prevention in Team Sports – Tim Gabbett

Gazzano, Francois. A Practical Guide to Workload Management & Injury Prevention in Elite Sport.

Science and Application of High-Intensity Interval Training

Haddad, M., Stylianides, G., Djaoui, L., Dellal, A., & Chamari, K. (2017). Session-RPE Method for Training Load Monitoring: Validity, Ecological Usefulness, and Influencing Factors. Frontiers in neuroscience, 11, 612. doi:10.3389/fnins.2017.00612